Wuyi Revisited: 2025 Trip Report

Listen to the Tea Technique Editorial Conversation podcast on this trip report:

Back Again

I said I’d be back – and so I am. A year after our introduction to Wuyi on the Tea Technique Research Trip 2024, I’ve returned to forge new friendships, deepen existing connections, seek out better teas, and to continue my dive into the deep water (水很深) of yancha. This trip was entirely more successful on those counts: I found a wider range of better tea, experienced less rain and flooding, and took a trip outside the park to a secret area to drink secret tea. In some ways, my impression of Wuyi has improved; in more ways, despite the level up, this visit reinforced the findings and assessments from our first research trip.

Wuyi is beautiful, poetry inducing ~ walking the park with a thermos of 素心兰, taking in the vistas, exploring paths branching off the main trail… there is no wonder that this place births legends.

Those findings and assessments were not entirely positive, and therefore, before we begin, I must beg your forgiveness as I once again clearly state that I prefer, desire, and enjoy the class of tea that is yancha. Not all yancha, mind you, for much that is given that classification is nothing of the sort: I do not like it when the leaves are burnt, I do not like it when the trees are cut short; I do not like it when the leaves are red, I do not like it when the soil is hurt; I do not like it when trees are culled young, their leafy song left unsung; I do not like it when the packaging lies, claiming provenance and cultivars that the leaves deny – and I do not like when trees are fertilized, forced growth that natures taste belies. I do not like the false mineral flavor – fake rock won’t yield true yanyun savor; I do not like tea hurried to sale, with moisture high, flavors frail. But – I would drink yancha on a plane, I would drink yancha on a train; I’d sip yancha on my yacht, where lao cong caicha (in the lee of a sail off an island in the tropical sun where blue ocean sparkles and we swim for fun) often hits the spot; I prefer to drink yancha with Wuyi water, and I often drink yancha with my mother; I would drink yancha in the shade, dappled pine-light gently swayed, or with friends who know how fine tea’s made; I would drink yancha brewed on purpose and yancha steeped within a thermos – if the yancha’s good you see, made from leaves that feel good to me; natural gardens, roasted right, antique zhuni, scholars delight, good yancha brewed with care, or great yancha, I’ll drink anywhere.

With that out of the way…

After my last trip report there was some chatter and pushback from vendors (*cough*) and fellow tea practitioners on a few topics worthy of revisiting. Specifically, there was discussion about the value of lao cong, the “superior” environment of Wuyi, and the ease of access to great tea. While responding to certain vendors is a lost cause, perhaps I can inspire a few fellow cha ren to challenge their assumptions, question their sources of information, and seek out better tea with an updated trip report for Wuyi 2025.

On this trip, with deeper connections to existing contacts and a nice set of new introductions, we worked with high-end tea merchants (no label or brand, just WeChat and trust), negociants (those making tea without owning the garden), and legacy families (those with historical land-holdings within the park, making their own “estate” tea). My developing network within Wuyi gave me access to tea and information that is not usually available to outsiders – particularly to tea tourists and western facing vendors. Being academic and entirely non-commercial has its benefits.

The Value of Verified References

My single most important finding from the last research trip was the prevailing overuse of fertilizer in Wuyi, on everything from new plantings to mature bushes and lao cong trees. That finding was reinforced in multiple ways this trip and fertilization level has become a central conversation within the Wuyi tea community, with various responses from farmers, makers, and merchants.

The effects of over-fertilization are insidious: reducing the concentration of flavor in each leaf, reducing the presence of unique terroir driven notes (including the proverbial 岩骨花香 and 岩韵 set of notes), and reducing the lifespan of the tree – in addition to the secondary effects of depleting the nutrients within the soil faster and spilling into the adjacent down-slope gardens (affecting other tea). The (over-)use of fertilizer boosts yields of worse leaf material, which generally sells without differentiation at the same price as better, less fertilized, more naturally farmed tea. The vast majority of zhengyan tea is over-fertilized. Nearly all of the tea used as a reference for good and bad Wuyi, including those from famous regions, including lao cong in distant jians (涧), including tea that looks great in photos as if it comes from a totally natural environment, is over-fertilized.

The over-use of fertilizer affects processing styles. When the flavor of the tea is lighter, the leaf thinner, and the moisture level higher, the resulting tea needs to be more oxidized and higher roast to develop into something that tastes like “Yancha”. There is truth to the idea of style drift over the last few decades in Wuyi tea, but contra the singular simple (merchant) explanation of changes in contemporary preference, the cause is rooted in the transition to intensive agriculture and overwhelming demand for tea from a constrained area with limited supply and no ability to expand.

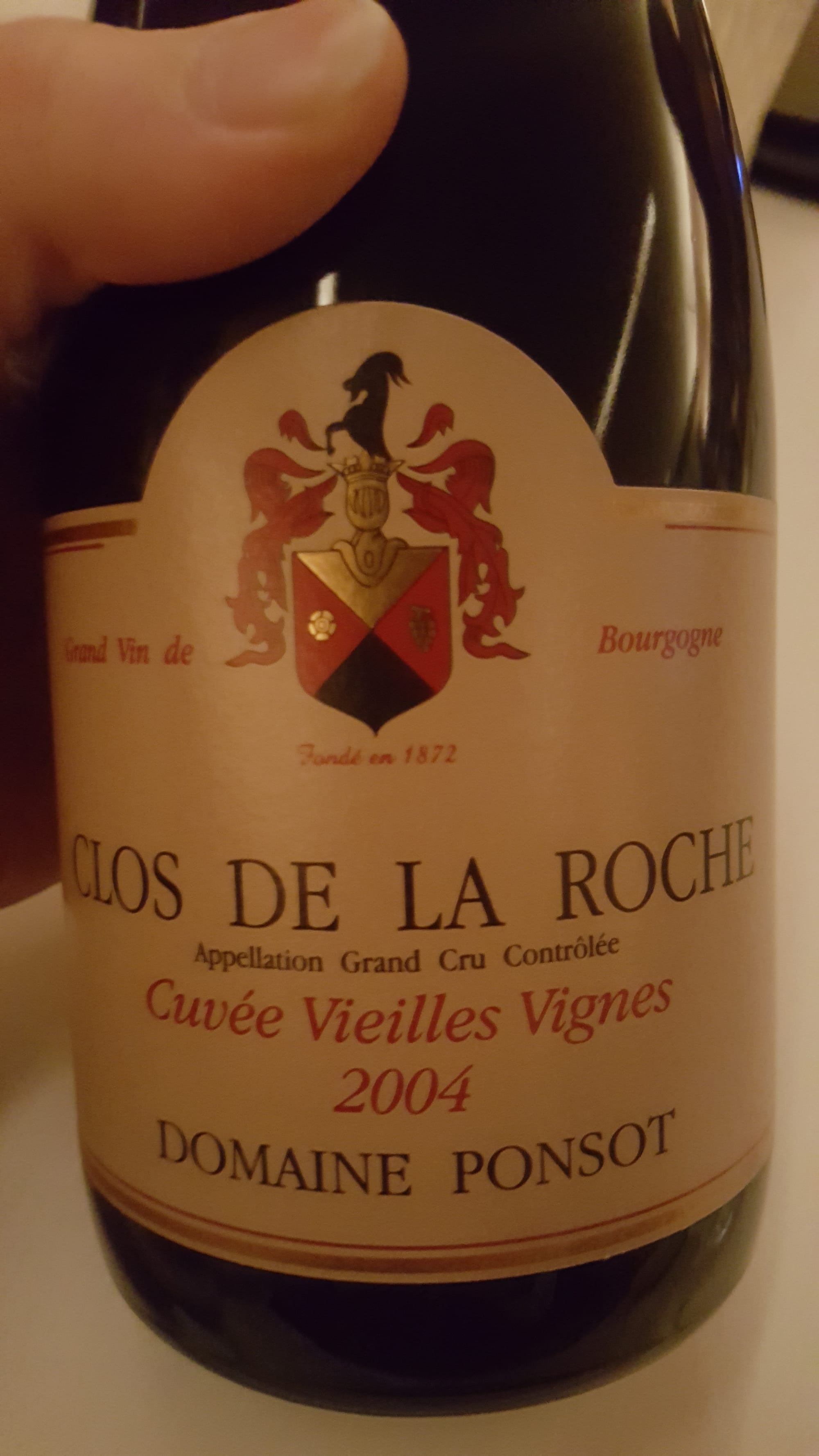

When someone online writes that they don’t think lao cong tea is better because the body is thin and the soup less aromatic – they are describing over-fertilized tea. It’s easy to buy lao cong this and lao cong that in Wuyi – but “lao cong” alone does not guarantee good tea. Just as wine varies in quality, rarity, and price even within the most prized areas, such as Burgundy (with bottles ranging from 20-euro unpalatable swill to 2,000-euro Tuesday night yacht club casual spills), drinking wine or tea from an area, cultivar, or age alone does not guarantee quality. It’s easy to say “I’ve drank Burgundy wine”, but if you’re at Guy Savoy in Paris (recommended!) talking to the sommelier (required) about the pairing for the evening meal (exquisite), you might not be having the conversation that you think you’re having…

In tea and in wine, the experience required to organoleptically identify attributes and qualities is a learned skill predicated on trusted sources for verified references. Asking for Burgundy is easy – identifying Clos de la Roche blind is hard. Training to do so requires cultural and financial capital. Yet even that is easy compared to yancha: at least when you pre-order your Domaine Ponsot 2-case minimum 3-years in advance of the harvest from your favored négociant, you know you’re getting AOC Grand Cru Roche. Train your palate on the best and you’ll be able to identify the rest.

Thin soup lacking aroma? You’re telling on yourself: you don’t have access to grand cru yancha, so on what foundational experiences have you built your attribute associations? Without trusted sources for verified references, you’re paying tuition for merchant roulette, gambling with your reference standards. Train on the rest and you’ll miss the best.

The yancha market is opaque and competitive. There's not enough great Wuyi tea to meet domestic demand, let alone export demand – and what does reach the Western market comes with eye-watering markups on top of the already heaven-high domestic prices for decidedly non-reference material. The best yancha is pre-purchased before harvest by repeat buyers with deep pockets and deeper guanxi; individuals with the financial, social, and cultural capital to buy reference tier yancha aren't selling it in the western market.

Online tea friends: feeling burnt by this roast? Come @ me when you can blind identify the difference between fertilized and unfertilized rougui – an easy test to separate the individuals spreading knowledge from those peddling fertilizer.

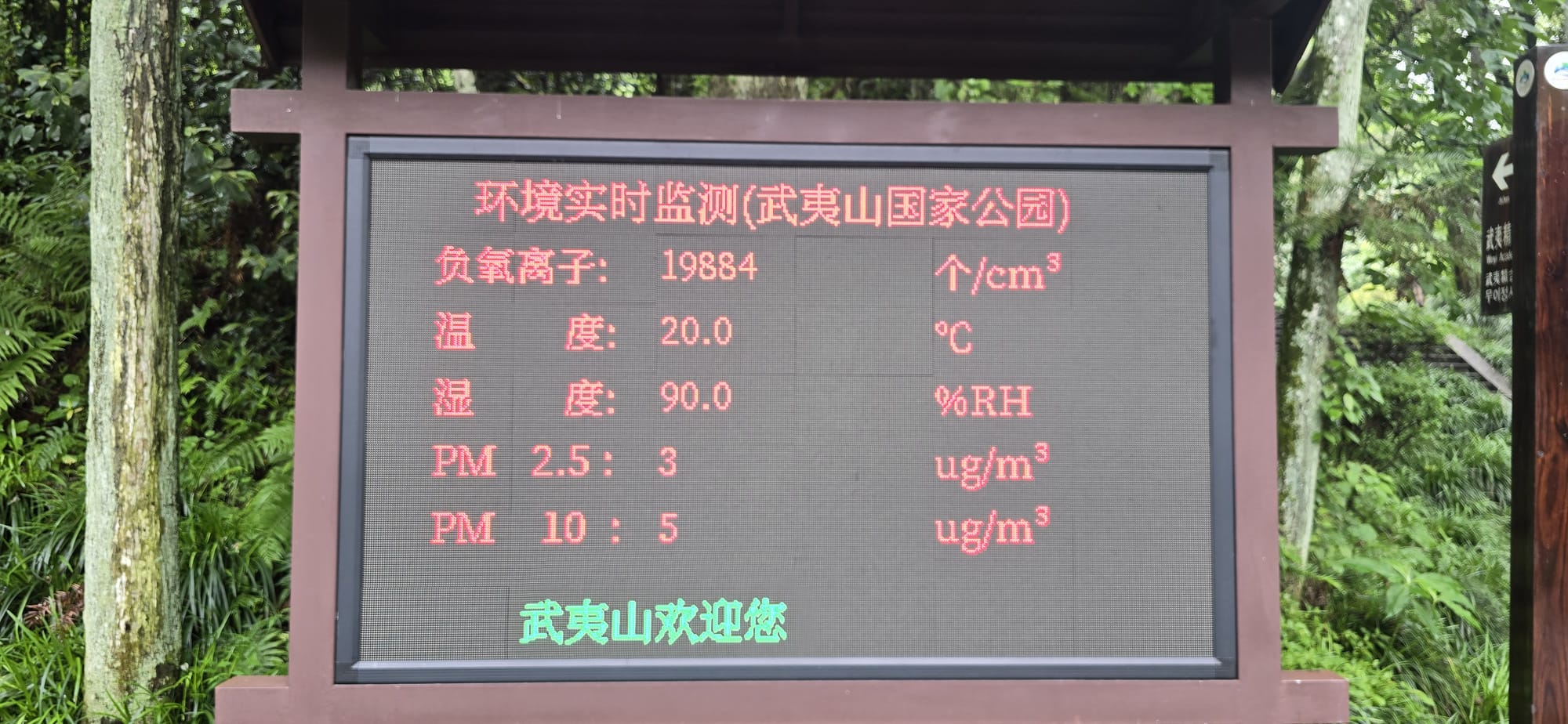

The “Superior” Wuyi Environment

There is no doubt that Wuyi is an exceedingly beautiful area with a long history of growing legendary tea in a unique environment. But like the Atlantic whaling industry, things change. In my last trip report, I compared the environment of Wuyi to that of Wudong (a village in Fenghuang) where many of the oldest dancong trees grow; this received various less-than-nuanced responses that the environment of Wuyi mountain is superior to that of Fenghuang mountain. To some extent, yancha vs dancong is a personal preference. I can’t and won’t try to change your preference between classes of tea via text on the internet – but I can give you some idea of what those closest to the tea and conversation in China are thinking. In this vein, I will now present to you, for your own consideration, a set of reasons that the modern Wuyi environment may not live up to its reputation.

Over Production

The area under cultivation dedicated to tea has more than sextupled in the 40 years since the founding of the park (across the 3 regions of the Wuyishan protected area), growing from ~1,640 hectares in 1978 to ~9,867 hectares in 2015; the amount of land dedicated to tea stabilized in 2012 with the implementation of new environmental protection laws, limiting new tea plantations or gardens.

Both Wuyi yancha and Wuyi black tea have a reputation for their natural production environment, supposedly reflecting the health and wealth of the land in the flavor of the tea; if so, one cannot talk about tea as a natural product produced in a pristine environment without considering the effects of monoculture and industrialized agriculture. One can, perhaps, appreciate the difference in density and intensity of tea farming practices by comparing the percentage land dedicated to tea within each region:

| Region | Tea Grown | Total Area (km²) |

Tea Area (minimum km²) |

Land Dedicated to Tea[1] (minimum %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuyishan National Nature Reserve | Black Tea | 578 | >6.09 | ~1.00% |

| Nine Bend Stream Ecological Protection Area | Black Tea, Yancha | 424.14 | >26.85 | ~6.33% |

| Wuyishan National Scenic Area | Yancha | 64.09 | >19.87 | ~31.00% |

The level of monocultural density in the zhengyan is unlike any other natural tea area, including Fenghuang (dancong), Tongmu (zhengshan xiaozhong), or Yiwu (gushu sheng pu’er). The Nine Bend Stream Ecological Protection Area contains the most land dedicated to tea, with at least 27 km² of tea fields, spread out amongst 424 km2 of land for a reasonable 6% tea coverage. Relatively little tea is grown in the much higher altitude Wuyishan National Nature Reserve, with only ~1% of its land dedicated to tea cultivation.

In comparison, about ~31% (!) of the zhengyan area is dedicated to tea fields. 31% of the land dedicated to majority terraced clipped hedgerow tea, planted around the standard density of 3,000 – 4,500 tea bushes per mu[2]. While this is less dense than a modern commercial tea plantation in China or Taiwan (~10,000 tea bushes per mu or more)[3] or mid-end commercial plantings such as the lower-slopes of Fenghuang (with modern higher density double row plantings at 4,000 – 6,000 tea bushes per mu)[4], it is an order of magnitude denser than the older single row planting method for dancong (500 – 600 tea bushes per mu)[5], newer quality focused dancong plantings (1,500 – 2,000 tea bushes per mu)[6] and lao cong groves in Wudong at ≤30 trees per mu[7].

| Region | Planting Density |

|---|---|

| Commercial high-density tea plantation in Fujian or Taiwan | ≥10,000 bushes / mu |

| Contemporary mid-grade low-mountain Fenghuang dancong plantation | 4,000 – 6,000 bushes / mu |

| Wuyi Zhengyan new planting | 3,000 – 4,500 bushes / mu |

| High-end mid-to-high mountain Fenghuang dancong planting | 1,500 – 2,000 bushes / mu |

| Older mid-to-high mountain Fenghuang dancong planting | 500 – 600 bushes / mu |

| Lao Cong groves in Wudong Village | ≤30 trees / mu |

Within the zhengyan, the tea gardens are nearly monocultural: Shuixian and Rougui cultivars account for more than 60% of the cultivated tea in Wuyi, with Shuixian alone accounting for 42%. Seed grown tea (qizhong, locally called caicha) by contrast constitutes less than 9% of fresh leaf yield[8].

At 31% coverage of medium-density mono-cultivar agriculture on what’s left of the original rocky red-loam soil, the zhengyan is producing too much tea in too small an area; it’s over the natural carrying capacity of the land, requiring the importation of foreign soil and industrial fertilizer, the continuous replanting of older trees, and the removal of lower yield indigenous cultivars to sustain its yield. Harmony with nature this is not.

Left to right: Plantation style garden in Niulankeng, view from Tianxin Yongle Pagoda; tea from the valley floor to the cliff-top in Niulankeng; tea garden near Tiancheng Temple; tea covering the valley on the path to Shui Lian Dong. We think it’s beautiful because we love tea – but is this really a natural environment at this concentration of monocropping?

These statistics include the tea growing by the river; the reason they bother to grow acres of tea in the floodplains is because they know they can sell it, often as zhengyan. For every image of flooded tea fields inside the park in last year’s trip report, someone online said “that’s not zhengyan!”. Sure – but what inner park tea do you think you’re drinking at ~50¢ / gram?

River tea, in the park proper. Same spot before and after the river flood, photos taken just a day apart.

Decrowning Tea

When we talk about decrowning tea, naively hopeful urbanites might have idealistic visions of loving farmers tending to the trees with a rather large bonsai scissor. That, dear reader, is not how this works. The trees are chainsawed like an ornamental hedge in a suburban office park by hired labor.

The aftermath of decrowning, Huiyuankeng and Shui Lian Dong. Notice the heavier cutting on the right, with the flat tops and barren branches.

Decrowning and over-fertilization go hand in hand. Decrowned tea roided out on fertilizer grows a lot of bushy branches with young leaves very quickly, just in time for next year’s harvest after which the process repeats anew. This is good for yield and bad for everything else: the health of the tree, the flavor of the leaves, and the rest of the environment, damaged by the gas-powered chainsaws, and the tea fields covered in tea leaves and branches until they compost into the soil or are carried off into the streams and rivers.

Soil Depletion

Yancha is named for the cliff-based environment, where water flows over the thin rocky soil, carrying nutrients down the mountain. The quintessential essence of Wuyi’s environment shaping the flavor profile of the tea is predicated on the constant flow of water, which in theory should erode rocks, form new soil, deposit minerals, and nourish the tea growing on the cliffs.

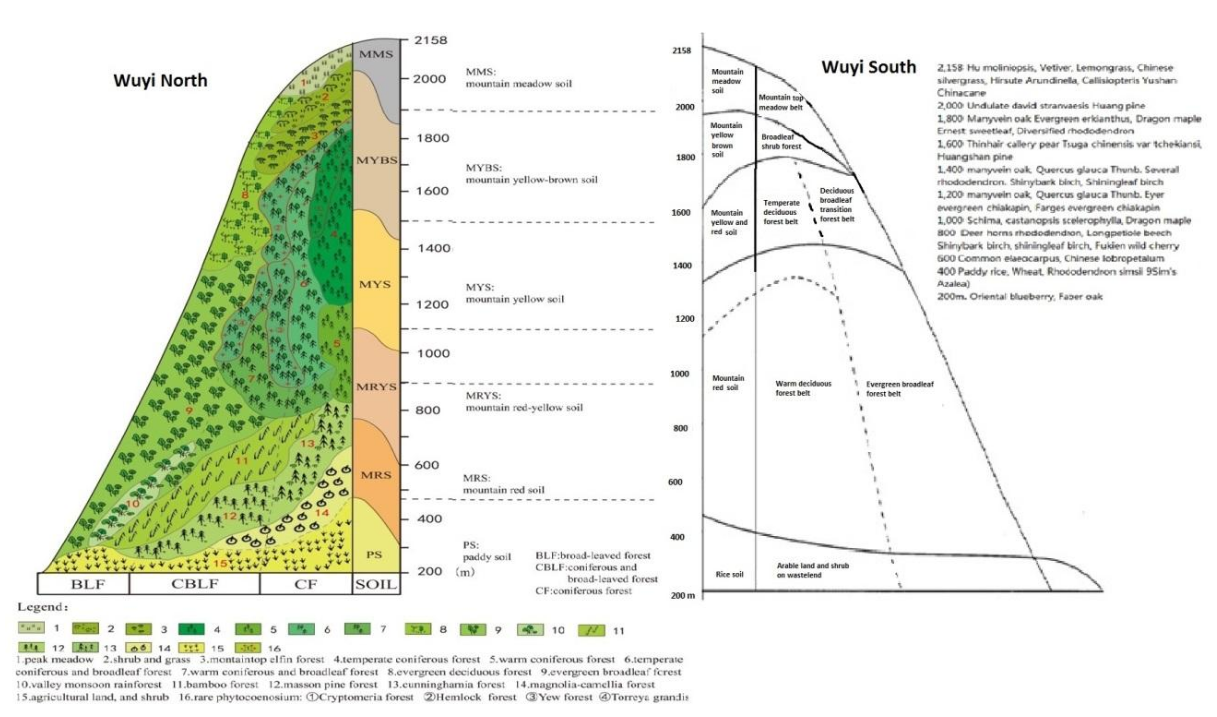

In equilibrium, this was true. Wuyi really does have a tremendous amount of flowing water over steep rocky soil which should be carrying minerals and nutrients down the mountain – if there was any left to carry. With the advent of modern intensive tea farming from the cliff base to its peak, the soil up-slope from the prime tea growing kengs and jians (valleys and gulleys) is depleted; if it wasn’t depleted, why would they need so much fertilizer for both the peak tea (lower quality) and the mid-slope keng (higher quality) tea? This explanation is already a simplification as the soil composition of Wuyi is vertically striated by elevation, with the zhengyan full-cliff tea originally grown in the red-soil (200 – 500m, averaging ~400m in altitude) and replenished by the red-yellow soil (400 – 600m) upslope from the prized tea gardens.

The depletion of the soil in prime tea growing areas within Wuyi is not a new issue: historically, tea farmers practiced the occasional ketu (客土, topsoil replacement) process, where soil from elsewhere within the park was moved into the worthy tea areas; eventually, every area was considered worthy and soil from outside of the park had to be imported. But if the special soil is the essential feature of Wuyi’s natural environment, the magic ingredients of cliff and water that imbues yancha with yanyun, what is the effect of foreign soil? This practice is now “illegal” though the occasional bag of soil is still seen when walking the tea trails. There is more to explore, but a full treatise on the Wuyi soil cycle will need to wait for the book. One day.

Supply and Demand

Ceteris paribus old trees are superior to young trees. It need not be your first consideration – I often consider other factors, including garden location, cultivar, and production skill before tree age – yet to dismiss the importance of laocong is to dismiss the importance of terroir. Lao cong trees are the true flavor of a place: a century of wind and rain and sun and soil; a century growing their roots into that specific place on the earth, a century of a tree harmonizing with its environment, working its way deeper into the land, absorbing more than the surface level fertilizer, run off, and imported ketu soil can provide. Finding lao cong tea made with skill from natural environments is a challenge; drinking them a joy. These teas offer an unreplicable experience, combining longevity, finesse, concentration, and qi. I clearly stated my opinion in last year’s trip report and will do so again here: places that care for their trees such that they can reach lao cong status produce teas with unique flavors that I value and prefer.

The value of laocong isn’t a unique idea the Chinese tea community forged in a 2007 三醉斋 thread. Consumers of innumerable other single-ingredient crops have independently noticed the superior flavor of older trees and their produce, developing parallel concepts: old-vine wines, old-tree coffee, old-tree cacao, mature tree fruits (apples, pears, cherries, and citrus), old tree-nut trees (almonds, walnuts, chestnuts, and pecans), old agave for mezcal, old vanilla trees, 100+ year old ginseng plants, and ancient tree olive oils (like “gushu”, extra virgin is a starting place for olive oil virgins), amongst an untold number of other plants whose product improves with age.

Having already proven my enological bona fides, I will use olive trees as an example to add evidence to my argument and showcase the breadth and depth of my culinary acumen. Olive oil was arguably the most important trade-product of the Mediterranean, from the age of the Greek empire through the collapse of the roman empire, transcending a multitude of cultures over a millennium. Brisighella has been famous for its olive oil since the Roman era and has maintained its reputation ever since; Andrea Giovanni Callegari, Bishop of Bertinoro, wrote in 1594 CE: “The air, the water, the wines, oils and fruits are so good and flavorsome that have no equal in all the other regions”. I, Jason Cohen, Author of Tea Technique, write in 2025 CE: “The proffered pairing most preferred presents washugyu breed Bistecca alla Fiorentina simply, anointed with only the heirloom Orfanello variety of Brisighella oil”.

The centuries old olive trees of Brisighella, visited by your humble author in 2024; half way between Florence and Ravana, the food is Tuscan influenced. Here the Steak Florentine is served dressed in ambrosiatic olive oil as the only garnish.

This olive oil is superb, its flavors unique. Its qualities are a product of old trees growing in the healthy soil of a favorable terroir, a place on the northern extreme of olive cultivation where the exposed mountain slope blocks the cold wind of the east, drenches the trees in afternoon sun, and the land cools quickly as night falls. Would we achieve the same flavor, the same quality of flavor, the same unique flavor, if we tore these ancient trees from the earth and re-planted the environment with more productive young olive trees from a rapidly growing cultivar at ~200 trees per acre? We’d certainly have more Brisighellian olive oil to sell.

This idea isn’t even new in Wuyi: old tree yancha has been prized since the contemporaneous development of whole leaf tea and the rise of the merchant economy (by the early Qing at latest). In contemporary usage, qizhong (奇种, “weird kind” or “unique variety”) refers to seed grown tea (“wild type” or “uncultivated”); before the 1940s, nearly all of the tea in Wuyi was seed grown, and qizhong referred only to those teas with an exemplary and unique flavor profiles:

山中则以小种为常品,其等而上者曰名种(此山以下所不可多得,即泉州、厦门人所讲工夫茶号称名种者,实仅得小种也)。又等而上之曰奇种,如雪梅、木瓜[i]之类,即山中亦不可多得。大约茶树与梅花相近者,即引得梅花之味;与木瓜相近者,即引得木瓜之味,他可类推。…各寺观所藏,每种不能满一斤,用极小之锡瓶贮之,装在名种大瓶中间,遇贵客名流到山,始出少许,郑重瀹之。其用小瓶装赠者,亦题奇种,实皆名种,杂以木瓜、梅花等物以助其香,非真奇种也。

In the Wuyi Mountains, “Small-variety” (xiaozhong) tea is the everyday grade. The next grade above is called “Famous Variety” (mingzhong), which is rarely obtained outside the mountains (what people in Quanzhou and Xiamen call their ‘mingzhong’ gongfu tea is in fact only xiaozhong). One grade above that is called “Unique Variety” (qizhong), such as “Snow Plum” (xuemei, 雪梅) or “Wood Quince” (mugua, 木瓜)[9] – even in the inner mountains these are hardly obtainable. Generally, a tea tree growing near plum blossoms will absorb a plum blossom flavor, and one near a quince will draw a quince flavor, and so on. … Each temple or monastery in the mountains stores only a very small amount of each of these teas (often under one jin in weight[10]). They keep them in tiny tin canisters nestled inside larger mingzhong tea jars. Only when an esteemed guest arrives do they bring out a pinch and brew it most carefully. If a small tin is filled and given as a gift labeled ‘Qi Zhong’, it is almost always just mingzhong tea – with a bit of wood quince or plum added to enhance the aroma – not a true qizhong.

Liang Zhangju (梁章钜), 归田琐记 (Guitian Suoji, “On Tasting Tea”), vol. 7, 1845.

While the term lao cong (老丛 or 老从 or 老枞) was developed during the RoC Period to market tea from the fields planted during the Guangxu Era (1871 – 1908 CE, Qing Dynasty) which tasted notably better than the newer plantings according to contemporaneous sources, the concept pre-dates the terminology by at least ~100 years. 6 years after Liang Zhangju wrote his treatise “On Tasting Tea”, Jiang Heng writes a travel log, including a chapter about tasting the single old trees of Wuyi, predating the widespread clonal propagation of these famous cultivars:

名种之奇者,红梅、素心兰及木瓜、肉桂。红梅近已枯。素心在天游,其真者予未得尝。肉桂在慧苑。木瓜植弥陀大殿前。其本甚古,枝干卷屈,类数百年物。予初疑木瓜味酸,最不宜茶。及在蓝上舍重庆家饮之,初入鼻微有木瓜气。及到口,但觉甘芬留舌本。半日犹津津,细咀之,并无酸意,此所以奇也。

Among the rare and famous yancha cultivars are Red Plum (红梅), Suxinlan (素心兰), Wood Quince (木瓜), and Rougui (肉桂). The Red Plum tree has recently withered. Suxinlan is at Tianyou Temple; I have not yet tasted the authentic one. The Rougui is at Huiyuan. The Wood Quince tree is planted in front of the main hall of Amitabha Temple. Its root is extremely ancient, with gnarled and twisting branches, resembling something hundreds of years old. I initially doubted that Wood Quince cultivar, named after a fruit with a sour taste, would be suitable for tea. But when I drank it at Chongqing's (重庆) house in Lan Shangshe (蓝上舍), upon first entering the nose there was a slight wood quince aroma. When it reached the mouth, I only felt a sweet fragrance lingering at the root of the tongue. For half a day it still left a pleasant aftertaste. Upon careful savoring, there was no sourness at all—this is what makes it remarkable.

Jiang Heng (蒋蘅), “Tea Song” (茶歌), 1851 CE. Printed in Wuyi Tea Documents (武夷茶文献, ed. Ye Guosheng, Fujian, 2011).

But, I understand, your merchant doesn’t have too many lao congs and you didn’t love the one you tried – probably best to disregard the collective parallel history of cultural preference acquisition for old tree agricultural products based on your available references.

Speaking of which, you’re aware of the abuse of the term “lao cong”, right? Today, tea plants of various ages less than 100 years old are often claimed as “old tree” without clarification. Training your palate on ~30-year-old tree shuixian labeled “lao cong” isn’t helping you learn to identify and appreciate older trees. I don’t have a solution for this beyond passing on merchants who don’t state the age of the “lao cong” tree by default; anything under 100 years is definitionally suspect, though ~60 years has become an unfortunate standard for non-legacy families riding the demand curve.

The tragedy of this is that we know for certain that the Wuyi cliff environment can keep tea plants alive for centuries – the 6 Da Hong Pao mushu are over 300 years old. The cliff environment, when forested with diverse plants and lightly planted with tea, where the top slope is left intact and fertilizer is not used, can grow tea as old as Wudong. The question then is: why isn’t there more old tea trees in Wuyi? If you’ve been following along so far, the answer is clear.

I’ll conclude this section by noting that this is a non-exclusive argument – other tea growing areas suffer from related or similar problems, including Fenghuang (as I discussed in the prior trip report!); but to a large extent the problem is concentrated here in Wuyi. The demand for too much tea from a restricted area rewards farmers and merchants for over-production, leading to the present situation. Great yancha from lao cong trees grown in natural jians without fertilizer still exists – its just being sold at astronomical prices to rich laobans, a few legacy buyers, and one eccentric book author.

Findings from this trip

The definition of zhengyan (正岩, “true cliff”) has changed over time: some traditionalists consider only the San Keng Liang Jian (三坑两涧, “3 valleys and 2 ravines”) as full yancha; in contemporary usage, zhengyan refers to tea from anywhere within the scenic area, excluding (by all experienced drinkers and honest merchants) the floodplain river tea. The stricter definition of zhengyan excludes the majority of the 36 peaks (these numbers vary across sources; the offical UNESCO application claims only 27 peaks, the lowest number I've seen, while other sources list up to 39), 72 caves, and 99 cliffs of the scenic area, including such exceedingly well-regarded appellations as Matouyan (马头岩, “Horse Head Cliff”), Sanyangfeng (三仰峰), and Ghost Cave (鬼洞, Gui Dong); even the Water Curtain Cave (水帘洞, Shui Lian Dong) is outside of the strict historical boundary. These are now all considered to be zhengyan teas, by official government standards as of 2010, because, why not? Flexible definitions are flexible, and those appellations can produce great tea.

Today there is an overwhelming demand for a limited supply of tea from a constrained area, incentivizing environmentally damaging farming practices. As a result, merchants and négociants are searching for teas growing outside the zhengyan in natural environments capable of producing the tell-tale yanyun (岩韵, “rock charm”) of yancha. My most interesting finding from this trip is the existence of such teas.

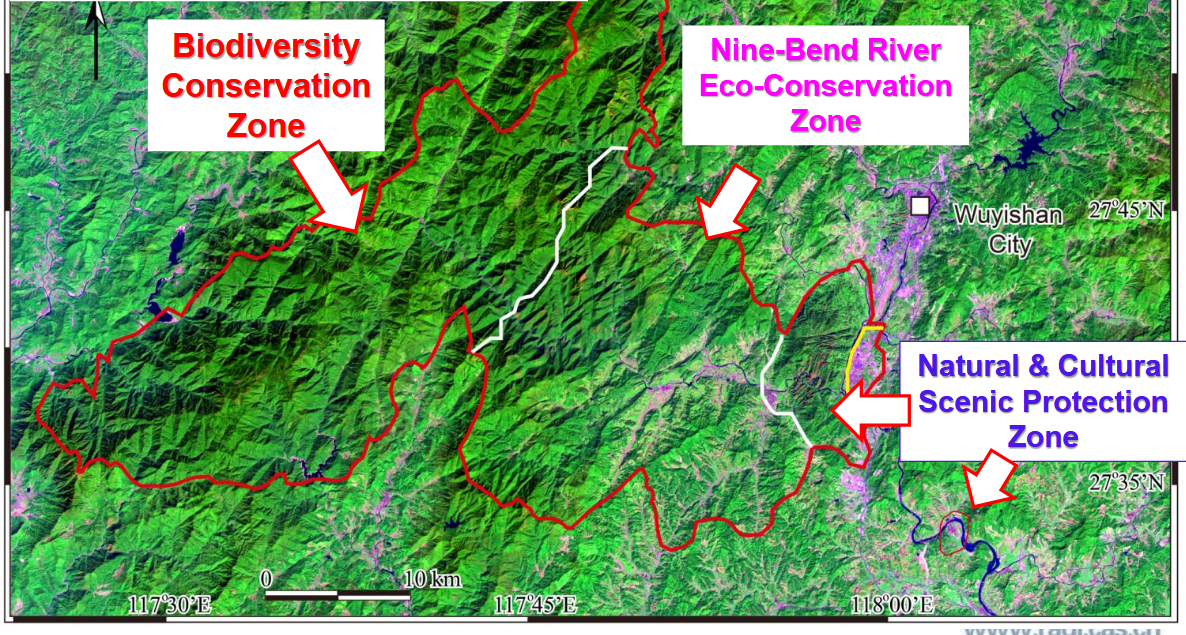

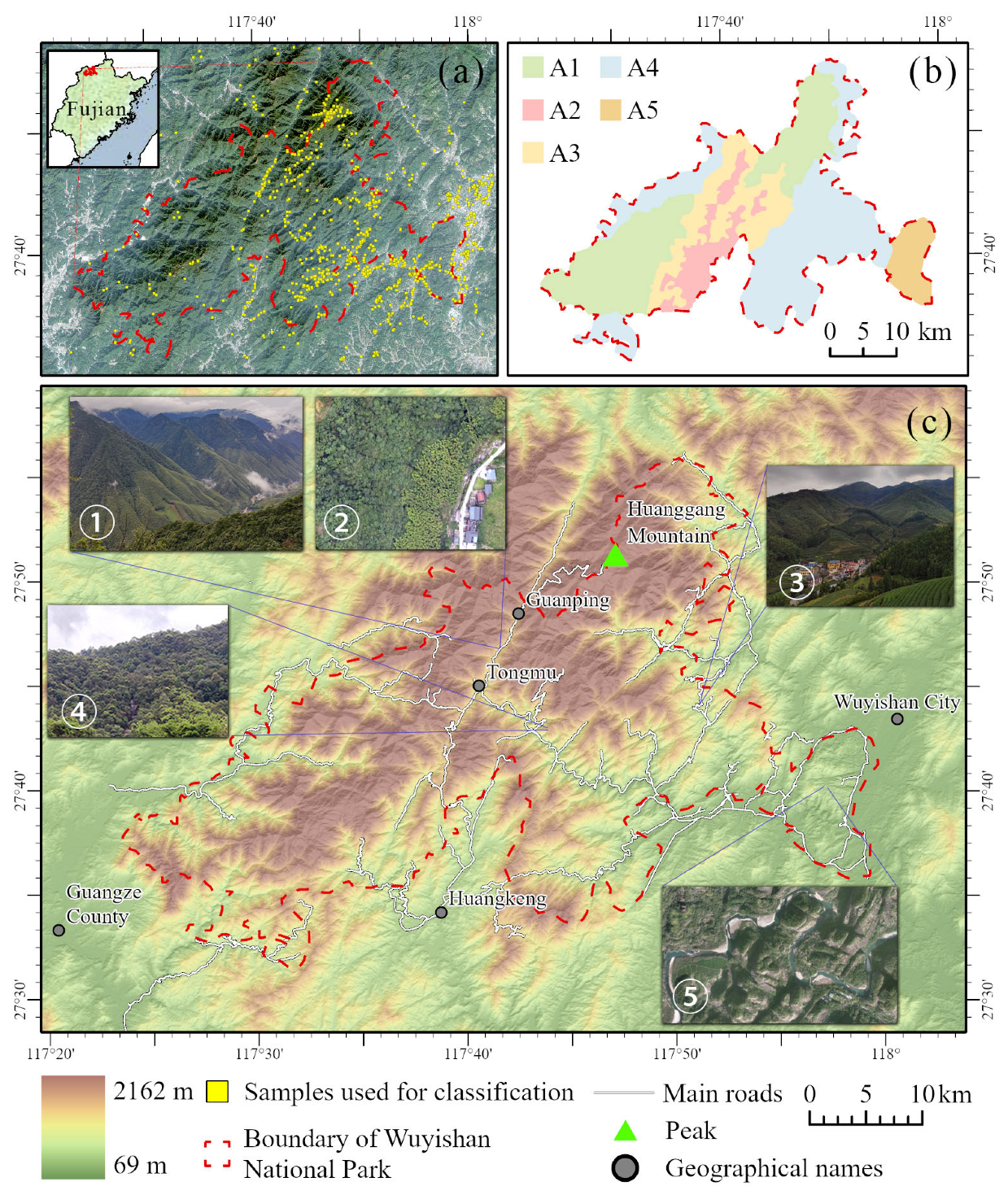

To find this unfertilized natural environment yancha, progressive cha-ren in China have turned to the rest of the Wuyi mountain range, which is far larger than the environmentally protected UNESCO World Heritage site. The environmentally protected area is divided into the Wuyishan National Scenic Area, the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area, and the Wuyishan National Nature Reserve. Only a tiny portion of the national park, the “Scenic Area”, is developed for tourism – the part with all the famous tea names. When we tea people (both inside and outside of China) think of Wuyi, we generally only think of the National Scenic Area as “the park”. Yet, the boundaries of what we think of as the “park”, the zhengyan, are an artificial construction, a decision to draw lines around an area developed for the competing demands of tourism, environment, and agriculture. The nature preserve has existed since 1979 – the national park only since 2016; ~3,000 people live inside the park proper, outside of the scenic area.

Surrounding the famous park area, on all sides, are thousands of acres of tea gardens under cultivation. To the east of the Scenic Area, the tea cultivation is predominately plantation style producing lower quality tea; to the north, a mix of very well-known and well-regarded tea grows alongside lesser plantations; to the west of the zhengyan, the tea gardens are within the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area.

The rocky slopes and flowing water of the Wuyi scenic area is a geological formation known as danxia (丹霞), from which the special yanyun flavor of yancha is said to develop. The scenic area is famous for its dramatic danxia landscapes, with flat-top cliffs covered by tea gardens reaching down into ravines that feed flowing water into the river valley; many merchants claim this danxia landscape within the park as “unique”. Yet the danxia landform is not unique: a set of 6 other danxia eco-parks stretching from Zhejiang to Guizhou were recognized by UNESCO (collectively called “China Danxia”) in 2010 and the local danxia formation in Wuyi extends along the entire river path throughout the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area, decreasing in concentration and relief with altitude. The park may be uniquely beautiful but it is not the only danxia formation on which tea is grown.

Focusing only on the local danxia formations: a 60km stretch of the Nine-bend Stream winds its way through the entire protected area, only ~9.5km of which is inside the National Scenic Area. It is here, in the lesser known and often unnamed regions outside the scenic area, where dispersed amongst the myriad rocky ravines leading down into the valley carved by the Nine-bend Stream, my local tea friends have focused their search for yanyun teas.

There is some to be found, though note that lesser tea gardens likewise line the banks of the 9 Bend River deep into the Ecological area:

The Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area produces some excellent tea excluded from zhengyan status. In response to the over-use of fertilizer and industrialized farming practices, my high-end tea merchants and negociant friends have all begun to source tea from this area – openly placing it side by side on the tasting table with zhengyan teas from core regions. They often provide better flavor, true yanyun flavor, at a lower cost. Much of these teas are lao cong, so it’s not as if this represents new monocultural encroachment into these areas; tea farming has been in these mountains hundreds of years before the UNESCO zone and National Park were established.

And what’s not to like? They can source tea from a natural environment unaffected by fertilizers, fertilizer runoff, decrowning, and monoculture; if we can find yancha cultivar tea (or even better, local landrace caicha) from pristine environments producing the signature yanyun flavor, well-made at a lower cost – don’t all cha-ren benefit? Yes, the less progressive merchants might have to update their educational material, but they’ll swallow their tears and find a source. Consider: no one was salivating over Gua Feng Zhai Gushu in Yiwu… until they were.

The most legitimate critique of good tea from the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area and the Wuyishan National Nature Reserve is where these areas differ geologically and environmentally from the core zhengyan.

| Region | Altitude Range | Altitude Average | Soil Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Scenic Area ("the park") | 171 – 724m | ~288m | Red Soil Red-Yellow Soil |

| Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area | 200 – 1927m | ~1,000m | Red Soil Red-Yellow Soil Yellow Soil |

| Wuyishan National Nature Reserve | 297 – 2155m | ~1,175m | Red-Yellow Soil Yellow Soil |

Very little tea is grown in the Wuyishan National Nature Reserve, and the soil-type and altitude differ greatly from the zhengyan; I have not personally tried tea processed as a yancha from this region of the park.

Within the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area, only a portion of the land is the right red or red-yellow soil for yancha, matching the (original, not ketu) soil of the zhengyan. As in the Scenic Area, the best yancha tea grows in red-soil danxia environments along the ravines carved by erosion. Lesser yancha tea is also produced in geologically “young” danxia environments along the mountain streams that feed into the river, and from higher altitude yellow soil regions that do not produce the signature yanyun flavor. Again, a range of tea varying in quality, terroir, and flavor are available: trusted sources help curate the best from the rest.

Focusing only on the danxia environments within the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area: the average altitude is higher than that of the Scenic Area. Can this higher altitude environment produce good yancha? I believe so. Someone may attempt a legitimate critique on the flavor-profile changes caused by the colder and dryer red-yellow soil environments, though I’ve heard little complaints about Sanyangfeng (at ~718m, red-yellow soil) which matches the majority of the good tea growing land in the ecological protection area. My assessment to date is that this is a non-issue; in what other context has higher altitude ever been a negative factor in the evaluation of a tea garden?

Finally, processing and processing skills certainly play a role in the quality of tea from a region. In this case, it’s often the same individuals making the tea from these alternative areas as from the zhengyan; it’s not an “either-or” choice for them or for you. Recently, I’m seeing more fully handmade teas available from the eco area – perhaps as a way to further differentiate the tea and to show a focus on quality. I think this is likewise a good trend.

In summary, I do not find most critiques of environmental differences between the famous “park” and the Nine-bend Stream Ecological Protection Area to be particularly convincing. Great tea can come from across China; great Wuyi can come from across the mountain range, wherever danxia formations are found. At some point, the overuse of fertilizer, the importation of foreign soil, and the intensive monocultural farming practices in the famous regions of Wuyi will have a large enough negative impact that yancha tea from the core region becomes a simulacra of itself. I believe we have already passed that point in some parts of the zhengyan.

Conclusion

While much of this trip report is negative, the motivation is positive. I love great yancha. While I am sad to see the state of the environment in the Wuyi Scenic Area, I am heartened to see the health of the environment and the quality of the tea in the rest of the national park, and to know a few of the forward-thinking cha-ren bringing some of this tea to market.

There are still pristine natural environments hidden deep in the park; there is natural laocong growing in small amounts of unadulterated soil without fertilizers if you know where to look (or know sources that can guide you). I still drink the limited tea I can find from those magical areas. Thankfully I have my legacy Wuyi landholding family friends to buy yacht club grade tea from at $4+/g; but my negociant and merchant friends are giving them a run for my money with $2/g laocong caicha from unnamed Jians in the eco area.

What I hope you’ll take away from this is that every tea should be evaluated on its merits – not on famous names or price. Tree age, terroir, and agricultural practices are interlinked with production skill and changing weather patterns: farmers will have good years and bad years, tea makers may have good batches and bad batches, merchants may have a mix of good and bad tea. This type of information is not publicly available, and a lot is done to cover over variations in quality with hype and merchant myth; because of this inherent variation and your own progression in tasting experience and knowledge, it is worth tasting (and re-tasting) teas before you buy, or at least purchasing a sample of each specific tea before committing to a larger amount. That’s not always possible when dealing with rare (or “rare”) and expensive tea purchased online, though, you should know, scarcity is a well-developed strategy levied by luxury e-commerce companies against impressionable consumers.

With the teas you already have, or sharing with friends, it’s worthwhile to test the yanchas of various vendors against each other to understand the range of qualities available and perhaps glean the truth of their marketing claims. The best way to learn is to drink with someone more experienced than you: doing so can greatly reduce your tuition fees, challenge the current state of your preferences, and help you find better teas – not just the tea that’s available online. That’s what I do when I’m in Wuyi, sitting by a rushing stream at a higher elevation with a cool wind blowing the humid air, clay kettle by our side, sampling past year’syears’ harvests; drinking tea with legacy tea makers, somewhere I’ve been asked to keep secret.

Come to one of the Tea Technique tastings, I’ll share.

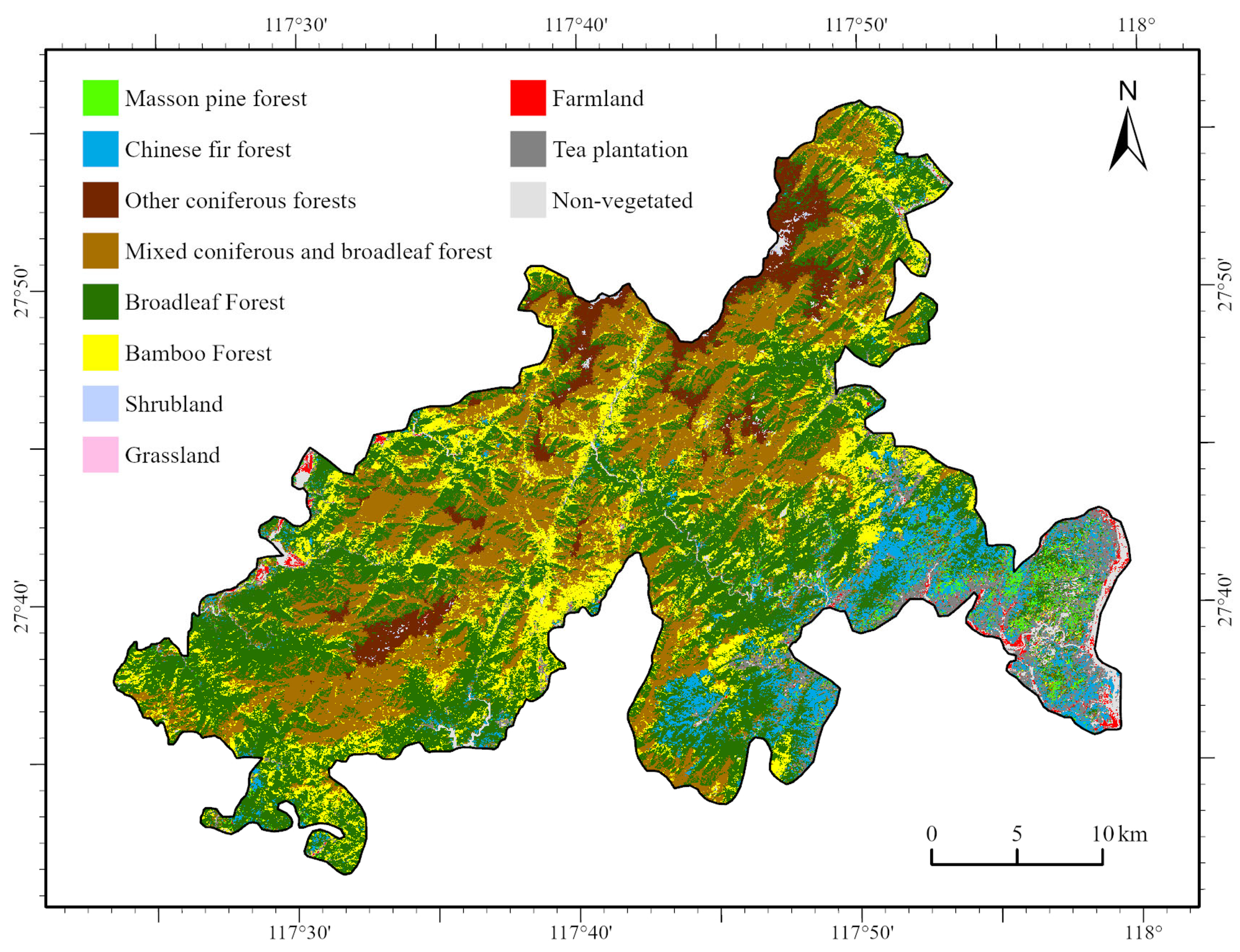

[1] Tea coverage estimates are cited from Ye, Yongpeng, Dengsheng Lu, Zuohang Wu, Kuo Liao, Mingxing Zhou, Kai Jian, and Dengqiu Li. 2023. "Vertical Characteristics of Vegetation Distribution in Wuyishan National Park Based on Multi-Source High-Resolution Remotely Sensed Data" Remote Sensing 15, no. 20: 5023. I interpret their proposed coverage area as minimums, as their paper uses machine learning to identify tea crop coverage, and their predictions are consistently lower than the official government statistics; the satellite imagery is likely missing mixed growth, where the tea is interspersed with trees and bamboo; this is likely to have a marginally larger effect on the Wuyishan National Nature Reserve and Nine Bend Stream Ecological, and lesser of an effect on the Wuyishan National Scenic Area.

[2] Multiple sources, including the official government National Standard GB/T18745-2006. Beijing: General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China and Standardization Administration of China, 2006; 福建省质量技术监督局. 《地理标志产品 福建乌龙茶》地方标准 (DB35/—–). 福州: 2017; Carr, M.K.V. Advances in Tea Agronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. (Chapter 6, “Planting and Replanting.”); 高清火, 叶华生, 姚月明, 王顺明, 修明, 陈树明, 梁东, 周银茂, 叶勇, and 张雯. "武夷岩茶 (地理标志产品)", "Wuyi Rock Tea (Geographical Indication Product)".

[3] 张龙云, 何超群, 李敏. “新建茶园矮化密植栽培模式对产量的影响”. 茶业通报 26(2) (2004): 72–73; Den Braber, Koen, Dwight Sato, and Eva Lee. “Farm and Forestry Production and Marketing Profile for Tea (Camellia sinensis).”

[4] 中国农业科学院茶叶研究所. "新茶园开发与幼龄茶园管理技术." 诸城桃林分院空中课堂, 2020; 茶叶科学编辑部. "茶树种植密度的研究." 茶叶科学 7, no. 2 (1987): 13-18.

[5] 广东省质量技术监督局. 《地理标志产品 凤凰单丛(枞)茶》地方标准 (DB44/T 820–2010). 广州: 2010

[6] Ibid.; Hanisch, Marjolein. Productivity and Resource Use in Ageing Tea Plantations. PhD diss., Wageningen University, 2010.

[7] 南方日报 (经侨网). “探访潮州凤凰单丛茶种植环节发展现状” (2022年3月17日); Deng, Jun. “Tea and Tourism Integration for Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of Chaozhou.” iBusiness 15, no.3 (2023): 192–207.

[8] Durighello, Regina, Mónica Luengo, Wataru Ono, Feng Han, Yiqing Zou, Yaohua Chen, Chaoyi Wang et al. "Tea landscapes of Asia: A thematic study. October 2021." (2021).

[9] See the end note after the chapter for a 2-page discussion on the lexigraphy of the characters 木瓜.

[10] Under Qing law, 1 jin (斤) = 16 liang (两) = ~596.8 grams; the current jin = 500-gram weight was adopted during RoC.

[i] The term 木瓜 (mugua) in this passage refers to the native Chinese‑quince fruit of the Rosaceae family, not to the tropical papaya (Carica papaya).

The Chinese Quince is indigenous to eastern-central China, its domestication is attested in written sources as early as the Western Zhou (1046 – 771 BCE); provinces with notable historical plantings include Anhui, Zhejiang, Hubei, and Jiangsu. Classical Chinese literature provides extensive documentation of quince cultivation; the Shijing (Book of Songs, 诗经, 1046–771 BCE) contains the famous poem "木瓜" in the Odes of Wei, establishing the fruit's cultural significance: "投我以木瓜, 报之以琼琚" (“You throw me a quince, I repay with precious jade”) is a classical reference to early gift exchange and courtship rituals. The development of Traditional Chinese medicine further elevated the quince's status: the fruit, known pharmaceutically as 皱皮木瓜 (zhoupimugua, "wrinkled-skin quince"), appears in the earliest Materia Medica compilations, and the Mingyi Bielu (名医别录, "Supplementary Records of Famous Physicians"; c. 500 CE) by Tao Hongjing (陶弘景) describes its properties as "sour, warm, non-toxic," prescribing it for dampness-related paralysis, muscle cramps, and digestive disorders. This medicinal tradition created sustained demand for quince cultivation, with specific regions gaining reputations for producing superior medicinal-grade fruit. Contemporary cultivation is thus spread across most of northern and central China, from Manchuria to the subtropical transition zones. As with many botanical terms in Classical Chinese, “木瓜” exhibited historical polysemy, referring to multiple native species within the Rosaceae family including the commonly cultivated Pseudocydonia sinensis (木瓜海棠) and the less-commonly cultivated Chaenomeles speciosa (贴梗海棠); even today, folk-knowledge of botanical terms deals primarily in pseudo-categories that vary with the locally present varietals and species, creating a rich environment for semantic expansion with the introduction of foreign plants.

In contrast, the Carica papaya is native to the lowlands of eastern Central America and a prime example of early modern globalization, one of the first American fruits introduced to China by the Columbian Exchange. The spread of the papaya to China followed established maritime trade networks: the Spanish empire brought papaya seeds from the Caribbean to Malacca and then the Philippines, where it was planted in in 1550 CE and from there the fruit traveled to India, finally reaching the southern Chinese ports of Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Ningbo in the late 1500s to early 1600s. Textual analysis from this period confirms contemporaneous recognition of papaya's foreign origin through the prefix 番 (fān): the initial Chinese name for papaya, 番木瓜 (fanmugua, "foreign wood-gourd"), established a clear linguistic distinction from the native quince species. Alternative names for papaya were also commonly used before standardization, including 万寿果 (wanshouguo, "longevity fruit") and 树冬瓜 (shudonggua, "tree winter melon"), reflecting attempts to categorize the new fruit within the existing Chinese botanical framework.

In the initial stages of the papaya’s introduction to southern China (1600 – 1800s CE), “番木瓜” was a distinct lexical compound for the foreign fruit, maintaining clear differentiation from the native 木瓜. The compound 番木瓜 follows established Chinese patterns for naming foreign imports, paralleling constructions like 番茄 (fanqie, tomato, literally "foreign eggplant") and 番薯 (fanshu, sweet potato, literally "foreign yam"). Papayas phonological reduction to 木瓜 began circa 1700s – 1800s as its cultivation expanded throughout southern China, with its commercial success as food and folk-medicine (papaya has minor anti-malarial properties and is believed to sooth gastrointestinal distress). Commonality drove semantic change as merchants, consumers, and agricultural texts increasingly dropped the 番 prefix in regions where papaya became the dominant commercial "木瓜”.

Yet, the adoption of 木瓜 for papaya was regionally separated across the historical divide of Northern and Southern China, and remains incomplete: across northern China, where tropical papayas cannot grow, the term 木瓜 has retained its classical “quince” meaning. Regional dictionaries from the 1700s – 1800s show increasing divergence, with southern compilations noting the "foreign wood-gourd" while northern texts maintain traditional definitions. This remains true today: Beijing markets, for example, sell Chinese quince as 木瓜 while labeling imported papaya as 番木瓜 or 南方木瓜 (“southern wood-gourd”). In summary: the regionalized historical lexical shifts of the characters 木瓜 represent an incomplete process of semantic evolution driven by cultivation, climate, and commerce.

Turning now to the specific text; we can verify that 蒋蘅 was referring to Chinese quince and not papaya from the description of the plant, the time-period, and the referenced location. To wit: the description "其本甚古, 枝干卷屈, 类数百年物" (“its trunk is very ancient, with branches and stems twisted and gnarled, like something several hundred years old”) is incompatible with the papaya tree which grows tall and straight, with an unbranched trunk, and typically live less than 50 years; in contrast a Chinese quince tree can live to more than 100 years of age and often develops an ancient and gnarled morphology for which it was prized as an ornamental plant. Secondly: written in 1851, it is exceedingly unlikely that a tree "in front of Amitabha Buddha hall" (“弥陀大殿前”) would be a non-native foreign import referred to by a shortened name, when Buddhist temples traditionally planted culturally significant native plants. Finally, while Fujian had early papaya cultivation, Wuyi is inland and culturally distinct from the Min coast, and its mountain climate is unsuitable for papaya and quite suitable for quince.

In conclusion: language is complex and words change meaning over time. Please consult your nearest materia‑medica entry for 木瓜 or the lexical notes in the 现代汉语词典 under 番木瓜 before attempting to issue corrections in the comments.